Emotion Classification using a Convolutional Neural Network

‘mean’ faces

‘mean’ faces

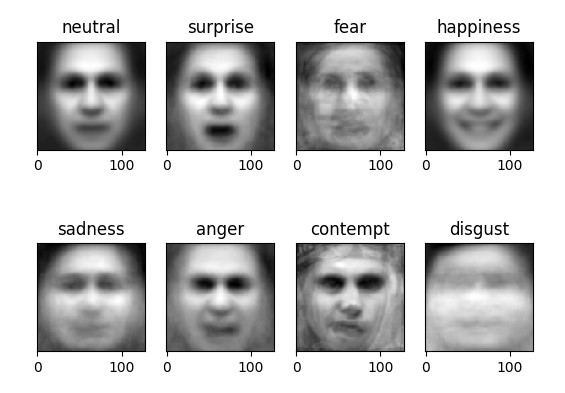

For a first ML project, two other PhD students and I worked on building a machine learning agent that could match pictures of faces to 8 different emotions (you can see our writeup here (pdf)). The image above is one piece of the EDA we did, which displays the mean face — “mean” as in “average” — for each emotion label.

EDA also indicated the need for data augmentation, as the data was grossly imbalanced: out of 12,594 images, 92% were labeled either “happy” or “neutral”, while 21 images (0.15%) were of “fear”, and a mere 9 images (0.066%) had the “contempt” label.

Sad Keanu is sad that pictures of other people on the interwebs tend to be happy.

Sad Keanu is sad that pictures of other people on the interwebs tend to be happy.

Some poking around indicated that a common practice was to transform images already in the dataset, so we opted to take this route. Even though we had serious misgivings about it from our statistical training. Which we should have trusted rather than being all “Whelp, guess anything goes. Machine learning is maaaagic <wigglyfingers wigglyfingers>!”

Who needs “very deep” networks after all?

As a starting place for the architecture of our neural network, we started with an established, “very deep” convolutional neural network architecture for image classification (Simonyan & Zisserman 2015), and pared it down considerably for our task:

-

The simplest configuration Simonyan & Zisserman used (ConvNet A) was a CNN with 11 weight layers:

- 8 convolutional layers with 3x3 receptive fields and between 64 to 512 channels;

- 3 fully connected layers with 4096, 4096, and 1000 nodes.

-

In contrast, our ending configuration had

only 3 much smaller weight layers :- 1 convolutional layer with a 3x3 filter and 16 channels;

- 2 fully connected layers with 128 and 8 (classification layer) nodes.

Surprisingly (at least to us), in the end, our much simpler architecture still achieved 80.1% test set accuracy!

There are a few caveats, of course, which we discuss in the writeup. Our main concern from the beginning was that our data augmentation strategy would inflate our test set accuracy; that fear appears to have been justified.

That said, even eliminating the data-augmented categories (“fear” and “contempt”), the classifier still achieved 80.25% accuracy. Though again a nagging voice keeps pointing out that it’s only because our classifier was basically just pretty good at separating “happiness” and “neutral”, i.e., as mentioned, 92% of the data. Shut up, nagging voice! I’m trying to be ok with having made a pretty decent binary classifier!

Main takeaways from this project:

- CNNs do not have to be gigantic, nor do they need to be trained for weeks, to “net” (ha!) decent results on a fairly complex task.

- Re-using data is perilous.

- Trust your Stats training. ML at its core is still just a bunch of statistical models. Just tied together in inextricable knots and lacking interpretability.

Mistakes not to make again / ideas for the future:

- Rather than augmenting our data by transforming images already in our dataset, we should have found new images / more labeled data for the scarce emotions in our data. And we definitely should have augmented only after the train-validation-test split. That was dumb.

- An alternative/additional idea to data augmentation might be weighting the loss function to penalize incorrect classifications of those scarce images more heavily, i.e. push the classifier to get those right even at minor expense to the better-represented classes.

- This probably would not get us all the way there with such drastically imbalanced data. But, as sad Keanu points out, since most pictures of people are likely to be of them being “happy” or “neutral” (i.e. just happen to be in the photo), this reweighting might still be of value.